The EU, the US and China: a middle way to approach the Middle Kingdom

In

Is the debate about China going in the same direction as the Cold War debate about the Soviet Union? Must all those who do not profess themselves sufficiently anxious about the yellow/red peril be suspected as fellow travellers?

In the American strategic community there is a strong consensus, across party lines, that China is the US’ strategic adversary. Whoever occupies the White House next, we can expect a hawkish line on China. The US is increasing the pressure on the EU to adopt a similarly confrontational stance. As a result, the debate in Brussels is becoming more polarised.

If the United States aims to remain the undisputed number one power, then seen from Washington the rise of China is indeed a problem per se. But Europeans have long been cured of that obsession: we haven’t been the number one for a long time, and there is no desire whatsoever to return to our imperial past. Therefore, China is not necessarily the EU’s adversary.

China pursues its interests. Of course, in many areas that has a negative impact on Europe’s interests, though oftentimes interests coincide as well. China has a strategy for China – that does not imply it has a strategy against Europe. China does what all of the great powers do, including the US and the EU themselves. And it is very successful at it, which is grating: the Chinese are beating us at our own game. At the end of the Cold War, the West thought that it was in control. Now it is clear that it is not, or at least not the West alone.

But that does not mean that we should start a new Cold War. Do we really want to be locked into a decades-long logic of confrontation again if we can still avoid it?

As I argue in European Strategy in the 21st Century, the EU should adopt a much more sophisticated strategy. Instead of choosing sides and freezing the dynamics of world politics by cementing two alliances (we and the Americans against the Chinese and the Russians), our strategy should be one of engagement with all great powers.

That is not the same as condoning everything that China does. As the European Commission proposals in its 12 March communication, EU-China – A Strategic Outlook, make clear, one should not be naïve. The starting point of any strategy is to unite and defend our sovereignty against all foreign attempts at subversion, in the political, economic or military sphere. The aim is to make the EU strong enough, not to confront China, but to engage China: to push back were we must, but to cooperate whenever we can.

Unfortunately, the regime of the Chinese Communist Party massively violates the human rights of its own citizens. The EU must continue to speak up for human rights, if only to make clear that human rights are universal, and that human rights violations will never be normality. But that does not preclude cooperation in foreign affairs: for that one does not need to agree on values, but only on shared foreign policy objectives and on what are legitimate ways of pursuing them.

The EU’s objective is not to bring down CCP rule. Our objective is that in its relations with other states, China respects the rules-based international order. Unlike the current Russian regime, which dogmatically uses its nuisance power against the US and the EU whenever the opportunity arises, China generally is a lot more pragmatic. In most dossiers, it will be guided by its interests rather than by ideology or emotion. That is an opportunity that the EU must grasp.

Or rather, that China must grasp. The EU has shown time and again that it is willing to take China’s positive pronouncements (on market access, on multilateralism etc.) at face value. If China is smart, it will now act upon those statements and join with the EU to promote real shared interests. If it doesn’t, than Beijing should not be surprised if more and more Europeans begin to see things the American way.

The article was first published in E!Sharp.

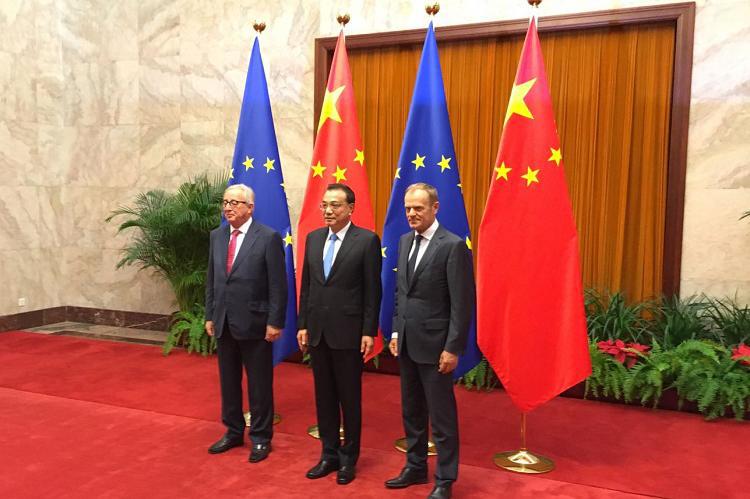

(Photo credit: EEAS Press Team)