AUKUS and the EU: A Snub for the Bloc?

In

The most surprising thing about AUKUS, the upgraded defence partnership between Australia, the UK, and the US, is the EU reaction. The Presidents of the Commission and the European Council have sharply condemned what they see as a snub for the Union, not just for France.

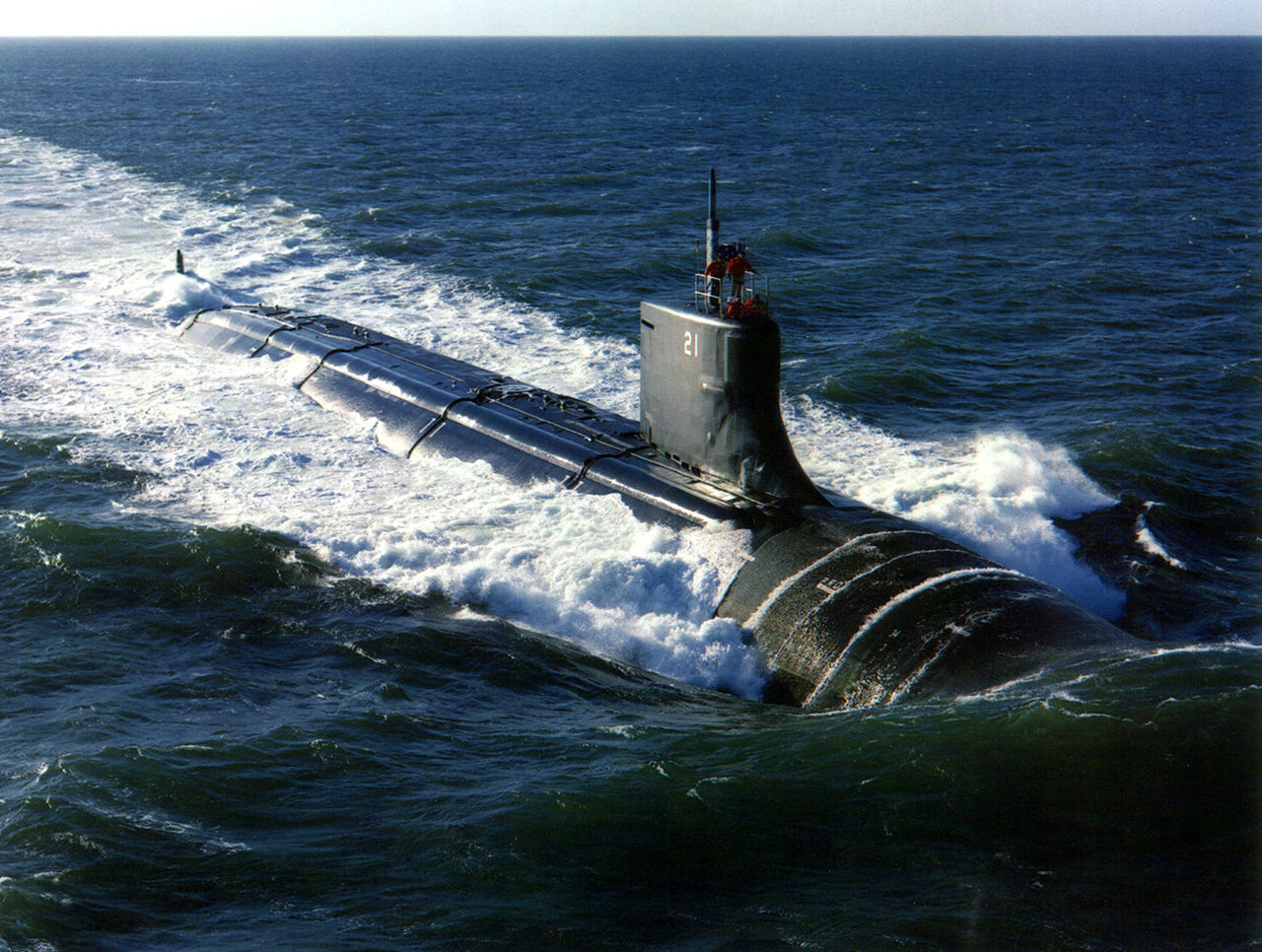

(Photo credit: Wikipedia)

*****

AUKUS and the EU: A Snub for the Bloc?

The most surprising thing about AUKUS, the upgraded defence partnership between Australia, the UK, and the US, is the EU reaction. The Presidents of the Commission and the European Council have sharply condemned what they see as a snub for the Union, not just for France.

That means they think of the EU as an integrated strategic player. Which is, indeed, the only way for Europeans to have any influence in world politics. But in reality it is not an integrated player yet, of course. When France makes a deal to sell submarines to Australia, or deploys its Charles de Gaulle aircraft carrier to Asia, those are French decisions, which are at best implicitly related to a broader EU policy. The same applies to other Member States. That is why the indignation about AUKUS and its immediate consequence, Australia breaking its contract for French submarines, is far from equally shared across the EU.

There are promising developments, such as the new tool of “coordinated maritime presence”, allowing for voluntary coordination between Member States that deploy ships (and aircraft) to a specific area, while these forces remain under national command. And just last week the EU unveiled a new Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. Fundamentally, however, most Member States continue to regard EU foreign and security policy as no more than one way among others to complement their national policies. There is no single EU policy or strategy.

That said, the manner in which France was, it seems, purposely deceived, is unbecoming the three AUKUS partners. Needlessly adding insult to injury, that was a grave mistake, and Paris is right to be upset. And whether Australia’s choice to become a non-nuclear weapon state with nuclear-powered submarines will reduce tensions and improve security in the region is questionable. But that the US and Australia deepen their alliance is hardly surprising, in view of the recent evolution of Canberra’s strategy. Nor is it unexpected that the US feels no need to consult with its European allies other than the UK (though Britain’s participation in AUKUS has a strong feeling of post-imperial symbolism).

Europeans must understand that Asia comes first now in American strategy, and that Washington will only take their views into account when they act as a bloc (as they do on many geo-economic issues). Europeans should not get carried away, therefore. If Brussels now decides to attach real consequences to the AUKUS incident, such as postponing the start of the new Trade and Technology Council with the US or the free trade agreement with Australia, that is a strong signal that the Union expects to be taken seriously as a bloc by its allies and partners.

But escalating the row only serves the interests of China. Fortunately (at least from this perspective), Beijing seems to disregard the EU as a strategic player, and misses every opportunity to improve relations and thus potentially drive a little wedge between Brussels and Washington. The recent Chinese refusal to have the German frigate Bayern visit Shanghai on its tour of Asia is a case in point.

Most importantly, a strong EU signal only really makes sense if from now on the EU then also behaves as a bloc, and Member States stop making purely unilateral decisions about troop deployments and arms exports as well as major diplomatic initiatives. Then the EU could find a role of its own, as an independent strategic player at the same level as the US, China, and Russia, with its own grand strategy. This may not seem very likely, but perhaps the current crisis could be used as a lever to that end. France surely is best placed to take an initiative in this direction.

Prof. Dr. Sven Biscop, director of the Europe in the World programme at the Egmont – Royal Institute for International Relations in Brussels and professor at Ghent University, has just published Grand Strategy in 10 Words – A Guide to Great Power Politics in the 21st Century.