The Belgian Recovery and Resilience Plan: A fresh impetus to prepare the skills of tomorrow’s workforce?

In

In the context of a fast recovery, training policy is one of the labour market instruments with the most positive effect on employment, but it is also a very expensive one. On 30 April 2021, the European Commission received the consolidated version of the Belgian Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP), with €950.64 million dedicated to up- and reskilling. Whilst trends such as digital automation, accentuated by the COVID-19 crisis, will profoundly reshape the future of work, the Belgian RRP could contribute to a successful transition towards new occupations, hence acting as a counter-cycled economic measure by mitigating broader social consequences. The success of this operation will be tributary to its magnitude, its promptness of response, and its capacity to target the most vulnerable persons.

(Photo credit: © European Union, 1995-2021)

*****

The Belgian Recovery and Resilience Plan:

A fresh impetus to prepare the skills of tomorrow’s workforce?

The motto of the State Secretary for Economic Recovery and Strategic Investments can be summarised as follows: Belgium must take advantage of the crisis to counteract its structural investments backlog. Whereas the EU average public investment rate has fluctuated between 3% and 3.5% of GDP over the last three decades, Belgium has experienced a rate between 2% and 2.5%. Compared to the EU average, the cumulative sum of the backlog is now estimated at €70 billion. The stakes are high for the €5.925 billion (1.4% of GDP) allocated to Belgium under the EU Resilience and Recovery Facility (RRF), which represents 45% of the public investment efforts announced by the federal government to address the crisis in the period 2020-2024.

Slowly but surely, headline indicators point to major distortions in the labour markets. The good news is that the impact of the lockdown measures was largely cushioned by public policies. After declining to its lowest point in 30 years, the EU-27 unemployment rate is expected to rise modestly given the size of the shock. It reached 7.7% in 2020, 1% higher than in 2019, and is expected to rise to 8% by 2022. The bad news is, unemployment is only part of the story. A study by Eurofound on the COVID-19 implications for employment and working life analyses the EU decline in employment as resulting mainly from transitions to inactivity rather than unemployment. Labour markets are confronted with an unprecedented setback that translates into the deterioration of indicators such as the inactivity rate, actual hours worked, or the rate of young people not in education, employment, or training.

The current crisis also requires that we do not lose sight of the need for a forward-looking economic approach. Jobs in 2030 will not look the same as today in multiple ways. Ongoing transformations, driven by digital automation, will not only have effects on job destruction and remuneration, but also on the nature and the quality of jobs. With the pandemic, we are stepping even further into uncharted territory as lockdown measures have accentuated existing trends related to digital transformation, such as e-commerce, automation, and teleworking. By 2030, between 8% and 9% of the workforce in Germany, France or Spain might need to transition to jobs in new occupations, which is on average 12% higher than what was expected before the crisis. Given these trends, most displaced low-wage workers may need to shift to higher-wage, more skilled, brackets. Although low-skilled workers are those most in need of upskilling and reskilling, empirical evidence shows that they are paradoxically the least likely to participate in learning and training activities.

Active Labour Market Policies (ALMPs) range from training offers and indirect employment incentives, to start-up incentives and direct job creation. Their role will be crucial to get back to efficient labour markets, which refers to matching workers with employment according to their set of skills. Upskilling, which is the impact of investing in improving existing workers skills, and reskilling, meaning the process of learning new skills to do a different job, were endorsed by the Council of the EU as a cornerstone for increasing sustainability and employability in a context of economic and social recovery. The €672.5 billion under the RRF will now serve as an incentive to mainstream these ambitions into actions.

1. The magnitude of ALMPs’ investments in the Belgian RRP

In its list of projects submitted to the European Commission, the Italian government dedicated €12.62 billion, or 0.70% of GDP, to its national agency in charge of ALMPs. It is more than twice the country’s current spending on ALMPs. The French government will invest €16.2 billion, 0.67% of GDP, in job activation and training measures, of which €7.5 billion come from RRF grants. It is a significant top-up to the country’s current expenditures on ALMPs at 0.52% of GDP. Even if the rather diverse structures between the national plans make the comparison difficult, the Belgian RRP may seem paltry as the country plans to invest €950.64 million, or 0.21% of GDP, on activation and training measures compared to current expenditures amounting to €2.523 billion, or 0.56% of GDP, on ALMPs.

Public investments on skills mismatch must therefore not be limited to European grants in Belgium. The RRP is a good first step towards recovery, but it is now crucial that it is accompanied by a broader investment effort, for instance through the development of synergies between the RRP and the regional investment plans. The division of powers in Belgium implies that the federal government has no say in the structure of regional investment plans. To avoid a ‘Christmas tree bill’ approach, country-specific recommendations (CSRs) addressed to Belgium over the last two years could serve as a shared strategic compass between the federal and the regions. The Flemish reform programme is in the vanguard in this respect, as it explicitly draws on the CSRs regarding training policy and digital skills. The two other regions of the country must now embark on the same path to embrace a coherent and ambitious strategy.

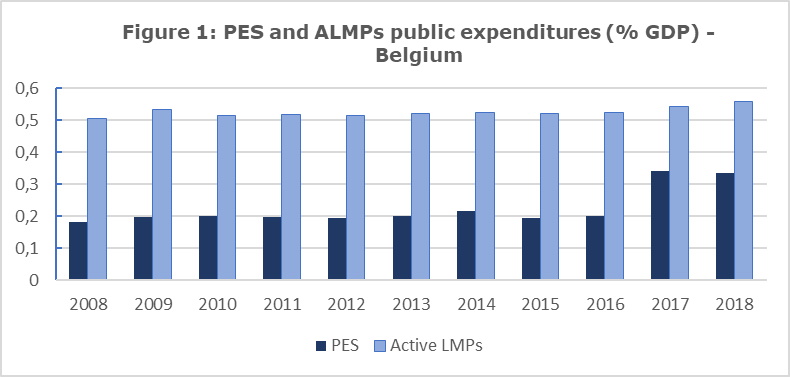

Belgium can also count on the quality of its public providers of employment services (PES) which will serve as enablers of a fast recovery by preparing tomorrow’s workforce. In that regard, Belgium is performing very well as we have seen an increase in PES funding since the 2008 financial crisis whereas ALMPs investments have remained steady (see Figure 1). These investments were made alongside a series of praised reforms of regional employment agencies in Belgium.

Source: Eurostat

2. Time is of the essence to reduce the benefits burden

The cumbersome nature of the RRF procedure clashes with the speed of action needed in the context of an economic recovery. The first disbursements, equivalent to a 13% pre-financing payment, will be made available more than a year after the initial approval of the €672.5 billion RRF by the EU heads of state. The Commission must first approve the 27 national RRPs, while Member States must ratify the Own Resources Decisions. The subsequent disbursements will then depend on the achievement of concrete milestones and targets. It is a lengthy process and, based on the European Commission’s forecasts, it is fair to expect that only a ¼ of the RRF grants will reach its beneficiaries by the end of 2022.

If parts of the RRF grants were released quicker, Belgian stakeholders should make immediate use of the funds promised for training policy, starting with those targeted at the unemployed. We must prevent temporary unemployment due to the COVID-19 crisis from becoming structural in the years to come.

3. Targeting, targeting, targeting…

Even the most optimists would recognize that a €5.925 billion package over 6 years does not constitute a stimulus capable of addressing both the recovery and the resilience of the Belgian economy. Nor does it could tackle the main structural challenges of our economy, namely population ageing and slowing productivity growth. The success of the RRP operation will lie in its ability to target, with limited resources, those who have the greatest added value for the labour market – who are also those in greatest need – namely unskilled and low-skilled workers.

Up- and reskilling investments are divided into three components under the Belgian RRP, namely: ‘Education 2.0’, ‘Training and Employment for Vulnerable People’, and ‘Training and labour market’ (see Figure 3). In these components, Belgium expressively dedicates €166 million to low-skilled workers within vulnerable groups, such as people with a migrant background, women, young people, or people at risk of digital exclusion. This is a significant breakthrough, as for years the country has been invited by the Commission to provide tailored-made ALMPs to its most economically vulnerable groups, without much success.

By doing so, Belgian authorities stress that preventive measures and tailor-made remedies for its population most affected by the skills mismatch are essential to the recovery and will remain under the authorities’ radar for years to come. Whilst the drafting process around the RRP left numerous commentators sceptical, there are good reasons to be optimistic about its outcome.