Why Belgium Should Create a Territorial Reserve Force

In

- EU and strategic partners,

- EU strategy and foreign policy,

- Europe in the World,

- European defence / NATO,

One of the lessons from the war between Russia and Ukraine is the importance of societal resilience and resistance. Since Russia started its invasion on 24 February 2022, Ukraine’s Territorial Defence Forces fight fiercely next to the regular armed forces.

*****

Why Belgium Should Create a Territorial Reserve Force

One of the lessons from the war between Russia and Ukraine is the importance of societal resilience and resistance. Since Russia started its invasion on 24 February 2022, Ukraine’s Territorial Defence Forces fight fiercely next to the regular armed forces. During its history, Belgium also developed similar territorial defence forces. After the Belgian revolution in 1830, the ‘Garde Civique’ (Civil Guard) was formed with territorial defence (against the Netherlands) as the primary purpose. Later, the focus of this ‘Garde Civique’ shifted to law enforcement. During the Cold War, the ‘Binnenlandse Strijdkrachten’ (Internal Armed Forces) defended the territory, economic and critical infrastructure, lines of communication (LOCs), and ports of debarkation (PODs). Consequently, Belgium has historical examples of territorial defence by volunteer reservists.

Nevertheless, because of its geographical position, Belgium does not face the immediate threat of invasion and occupation. However, Belgium has an important role regarding Host Nation Support (HNS) during Article 5 (of the Washington Treaty) scenarios. Having territorial reserve forces that could support collective defence operations, provide a backup capability during times of crisis (traditionally described as ‘Aid to the Nation’), and thus fulfil Belgium’s commitments under Article 3, would be a welcome and additional capacity. The regular armed forces would then be relieved of these tasks and can focus on their core task, namely expeditionary, collective defence or collective security operations.

Other states in Europe have similar reserve forces, such as the Scandinavian countries. The Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish Home Guards are good examples of how volunteer reservists can be used for territorial defence. Furthermore, neighbouring countries have comparable capabilities. The Netherlands has a ‘Korps Nationale Reserve’ (National Reserve, or ‘Natres’) that is around 3000 volunteers strong (numbers from 2020) and receives an annual budget of 35 million euros. France established a ‘Garde Nationale’ (National Guard) in 2016 mainly focused on Homeland Security operations.

A Belgian Territorial Reserve Force

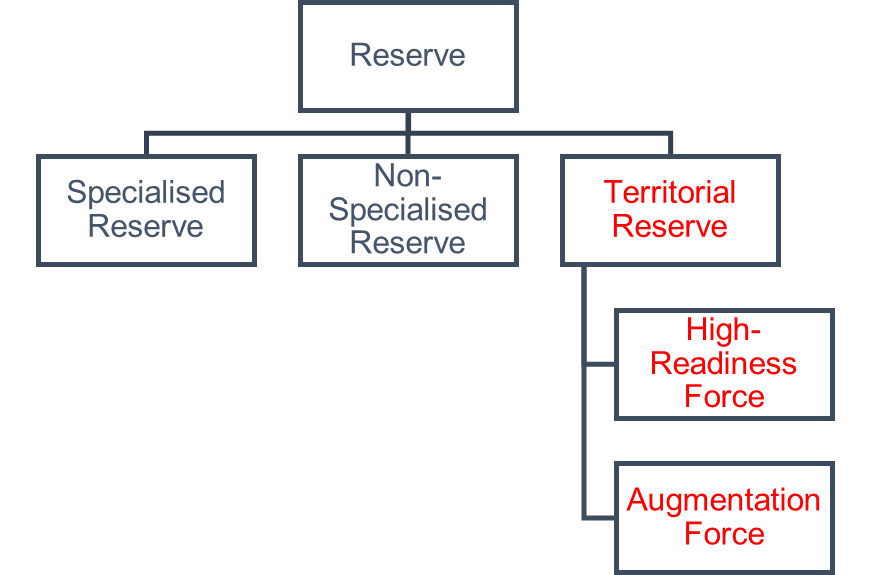

Currently, Belgium is expanding its reserve forces. Regarding competencies, two types of reservists currently exist, namely the specialized and non-specialised reserve. Specialised reservists fill specific positions with specific professional competencies that are not – or not sufficiently – present in the regular armed forces. Non-specialised reservists fill mainly combat functions within the active battalions to which they are assigned. Regarding readiness and training, completing at least 7 days of yearly training qualifies the reservist as trained, with fewer days it lowers him/her to the non-trained category. A higher training level is achieved by those volunteering for one of the Corps Operational Reserve (COR) companies attached to the active infantry battalions mainly for Homeland security tasks.

Whereas these reserve forces are necessary to strengthen the existing regular armed forces, they have difficulties building up manpower mainly because of the location of the infantry battalions in the East of the country limiting the interest of recruits in the West. Therefore, we suggest the creation of a Territorial Reserve (in red on the figure)  composed of High-Readiness Forces and Augmentation Forces. Such a twofold structure exists, for instance, in Norway. The Netherlands is also exploring a dual structure that puts elements of ‘Natres’ Battalions on higher readiness. France combines specialised reserve and volunteer ‘Garde National’ units by integrating them inside the active battalions.

composed of High-Readiness Forces and Augmentation Forces. Such a twofold structure exists, for instance, in Norway. The Netherlands is also exploring a dual structure that puts elements of ‘Natres’ Battalions on higher readiness. France combines specialised reserve and volunteer ‘Garde National’ units by integrating them inside the active battalions.

Based on the number of reservists in the Netherlands, a Belgian High-Readiness Force of around 2000 reservists and a second layer of Augmentation Force of around 1500 reservists should be a feasible first target. These light infantry forces should be spread across the territory, ideally on the level of the provinces. This has important advantages during security crises and disaster relief operations, for instance, the territorial reserve units will have valuable local knowledge and a shorter activation period. In addition, the proximity of the unit to the home of the reservist is very important regarding the recruitment and retention of reserve personnel.

This type of territorial reserve would, firstly, strengthen Belgium’s societal resilience and help fulfil its Article 3 commitments, stating that “In order more effectively to achieve the objectives of this Treaty, the Parties, separately and jointly, by means of continuous and effective self-help and mutual aid, will maintain and develop their individual and collective capacity to resist armed attack.” On 14 June 2021, the Heads of State and Government of the NATO approved a Strengthened Resilience Commitment that should further enhance “national and collective resilience and civil preparedness in an increasingly complex security environment.”

Secondly, Belgium is a crucial link in NATO’s New Force Model regarding the ‘Reception, Staging, Onward Movement’ (RSOM) of Allied troops going east in an Article 5 scenario. Consequently, ‘Host Nation Support’ (HNS) is crucial for Belgium’s contribution to NATO. Especially, the seaports of Antwerp, Zeebrugge, and Ghent, the main international airports, energy production and data centres are vital infrastructures to secure. Territorial reserve forces could support or take over most of the tasks from the regular armed forces building up towards expeditionary Article 5 operations. The protection of critical infrastructure would, therefore, be one of the core missions, next to force protection of the Allied elements.

Thirdly, these reserve forces would also be ideal assets for ‘Aid to the Nation’ missions, supporting police forces during homeland security operations. Following the terrorist attacks of 13 November 2015 in Paris & 22 March 2016 in Zaventem and Brussels, regular armed forces patrolled the streets, called Operation Vigilant Guardian (OVG). This operation ended after nearly half a decade in September 2021. Operation Spring Guardian, the protection of nuclear power facilities, was temporarily interrupted, then recently resumed. While this was a necessary mission, it did have an impact on the readiness and availability of troops for other, expeditionary tasks. Similarly, the Belgian armed forces were engaged during the tragic floods of 2021 and the COVID pandemic. Territorial reserve forces could lessen the burden and assist the regular armed forces during such disasters and provide additional support.

Next to land territorial reserve forces, there should also preferably be naval and air territorial reserves. The primary tasks of the naval territorial reserve would be Harbour Protection and Coastal Surveillance. These forces could strengthen Belgium’s capabilities to assist during so-called ‘Fort to Port’ RSOM operations & help monitor and secure the Belgian exclusive economic zone (EEZ). This is a crucial task because, for example in November 2022, a Russian ship allegedly tried to map critical infrastructure in the Belgian part of the North Sea. Subsequently, the air force territorial reserve would have as its primary goal Force Protection of the military airfields and other important aviation-related infrastructure. In addition, a flying reserve ISR capability would be useful to support Homeland Security operations. Denmark has, for instance, a flying Air Force Home Guard Squadron with two Britten-Norman BN2 Defenders for Homeland Security and Search & Rescue missions.

Conclusion

2023-2026 provides a unique window of opportunity to create a territorial reserve with three core missions: (1) homeland security (incl. Article 5 operations), (2) HNS, RSOM and Force Protection, and (3) Aid to the Nation during disasters and emergencies. The ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine and the recent crises showed Belgian citizens that having an adequate military capacity to react on short notice in extreme scenarios is crucial. As a result, serving in territorial reserve units could be appealing to citizens that do want to help during national security crises but do not want to be fully part of the standing armed forces. Furthermore, because of the ongoing renewal of vehicles and other equipment in the active-duty units in the coming years, these territorial reserve units could easily be cost-effectively outfitted with existing equipment. The start-up costs for the high-readiness elements would be 8-10 million (€2022) and the yearly operating costs 10-12 million (€2022). Consequently, it would be an affordable way to increase Belgium’s societal resilience, homeland security capabilities, and contributions to NATO.

Luc Audoore is a retired active-duty Lieutenant-Colonel (OF4) with a background in the Infantry and later transited with the Army Aviation into the Air Component. Following ten years commanding a civil-military (ISR) aviation detachment acting as Luxembourg Defense participation in EU and NATO operations, upon retirement he joined the Belgian Defense active reserve and is currently assigned as Operations and Training Officer in the Military Command of the Province of West-Flanders. He wrote, on his personal initiative, an internal case study for Belgian Defense on the potential for a Belgian Territorial Home Guard.

Wannes Verstraete is an Associate Fellow at Egmont – the Royal Institute for International Relations. He is also a PhD Researcher and Teaching Assistant at the Political Science Department of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB).

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons)