Russia Invades Ukraine: The Dangerous Weakness of a Military Superpower

In

What is an extra slice of Ukrainian territory to Russia? A war of aggression no longer fits in our European logic, but it does in that of President Putin. He seeks to permanently position Russia as a great power to be taken into account, and to restore a sphere of influence in the former Soviet Union.

*****

Russia Invades Ukraine: The Dangerous Weakness of a Military Superpower

What is an extra slice of Ukrainian territory to Russia? A war of aggression no longer fits in our European logic, but it does in that of President Putin. He seeks to permanently position Russia as a great power to be taken into account, and to restore a sphere of influence in the former Soviet Union. For Putin, the greatest threat is not potential NATO membership of Ukraine, but the country’s gradual westernisation through its close association with the European Union. For if that succeeds in one large former Soviet republic, then who knows where else the public might turn against its authoritarian leaders…

It is precisely because the new regime in Ukraine was about to conclude a far-reaching free trade agreement with the EU, that Putin attacked the first time, in 2014. Perhaps most determining of his actions today, is that in fact that first invasion was a failure. Russia annexed the Crimea, but against its expectations the rest of the country totally turned against it. Only in a small region in the east could Russia instrumentalise limited numbers of armed separatists. Putin, therefore, is trying to undo his own failure.

And we just stand aside and watch? “The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must”, Thucydides wrote already. Sadly, all too often that still is the hard reality of international politics today. When a great power decides upon war against another country, there is little the other powers can do to prevent it. Unless they are prepared to go to war themselves, but a direct confrontation between nuclear powers is so incredibly dangerous that all refrain from it unless their own territory is directly under threat. Once Putin had decided, therefore, the renewed invasion of Ukraine could no longer be stopped (just like in 2003 nobody could halt the US once it had made up its mind to invade Iraq).

That does not mean it was a mistake to enter into negotiations with Russia – attempting to prevent bloodshed is never wrong. Today, however, we can assume that actually Putin decided early on in the current crisis to revert to military action anyhow (but perhaps not at which scale). Maybe he had even set his eyes on this years ago, and was just waiting for what he considered the right moment. This is not a failure of diplomacy. When two sides want to talk yet part ways without an agreement, that is a failure. But when one side is not willing to concede anything, and uses diplomacy only to mask its true intentions (and thus to lie to its interlocutors), real negotiations have never actually started.

Now that Putin has opted for war, there is little space left for diplomacy. At some point regular combat will come to a halt and a new demarcation line will emerge (if Russia does not occupy all of Ukraine). The EU and the US cannot in any way legitimise the result of this war of aggression. There will be no peace conference drawing new borders. At most we will see a ceasefire between Russia and what remains of Ukraine.

What will the future bring then? Tough sanctions from the EU and the US, and a freezing of relations with Russia for probably many years to come. That will not immediately help Ukraine: sanctions will not make Russia retreat, and will hurt us too. Yet they are absolutely necessary to send a signal to the entire world: one cannot violate the core rules of the world order without paying a price. Otherwise the rules would be hollowed out and no order would eventually remain. Reducing relations with Russia will hit the EU hardest in the energy domain, but it can be done – one more argument to accelerate the green transition. Russia has built up great reserves and can do without the revenue of gas export to Europe for now, but cannot sell that gas to anyone else; those fields are connected to us alone.

Is Putin really winning, therefore, or is he trying not to lose? War with Ukraine will not solve Russia’s domestic problems; instead, it will worsen its economic prospects. The sphere of influence that Putin says he is defending he already has to share with China, a major economic presence in all former Soviet republics. In that sense, conquering Ukraine is a sign of weakness: Russia does not have any positive project that can attract other countries of their own accord. The same applies to Russian interventions in Africa and the Middle East: sufficient to disrupt our plans (as in Mali, where the military regime kicked us out), but not to construct their ow project. Indirectly Russian military adventurism also undermines China’s, mostly economic strategy. That is why today China does not really pronounce itself: it will not openly go against Russia, but will not openly support it either.

Nonetheless, a declining great power that remains a military superpower can be very dangerous. The EU will have to seriously reassess its strategy, therefore. First of all, we must enhance our territorial defence. In previous decades, most European armed forces have focused on expeditionary operations. Those remain necessary, but at the same time we must reinforce our conventional deterrence. Today, the US fully assumes its leadership role within NATO, but what if there were a major crisis in Asia at the same time, or if Trump were in the White House? A dimension of our defence that demands urgent reinforcement, is deterrence of hybrid actions. Russia will undoubtedly intensify those: cyber-attacks, disinformation, sabotage, coercion etc. As the host of NATO and the EU, Belgium is a primary target, as its National Security Strategy adopted last December emphasises. We must dare to retaliate against hybrid actions, including with our own offensive cyber operations. The EU must also elaborate an entirely new strategy for North Africa, in order not to lose all influence.

This is not the end of the European security architecture. Russia cannot bring down the EU or NATO. Only our own antidemocratic extremists can do that, who often act as useful idiots in the service of Russia. But relations with Russia will become very cold again, and we will be forced to invest more in defence. At the same time, we must continue to invest in our own positive project, the EU, and in multilateral cooperation with all states, authoritarian regimes included, whenever interests coincide. Cooperate when you can, push back when you must. Keeping the world together in one order to which all states subscribe: that is the challenge for international politics in the 21st century. Russia has now put itself outside that order for some time to come, but it does not have the power to overturn it. China could, but so far has opted for an assertive economic rather than military strategy. The US hopefully realises that in addition to its military contribution, for which Europe must be grateful, it ought to propose a positive project for the world as well. No country can safeguard its way of life alone, and with military means alone – not even a great power.

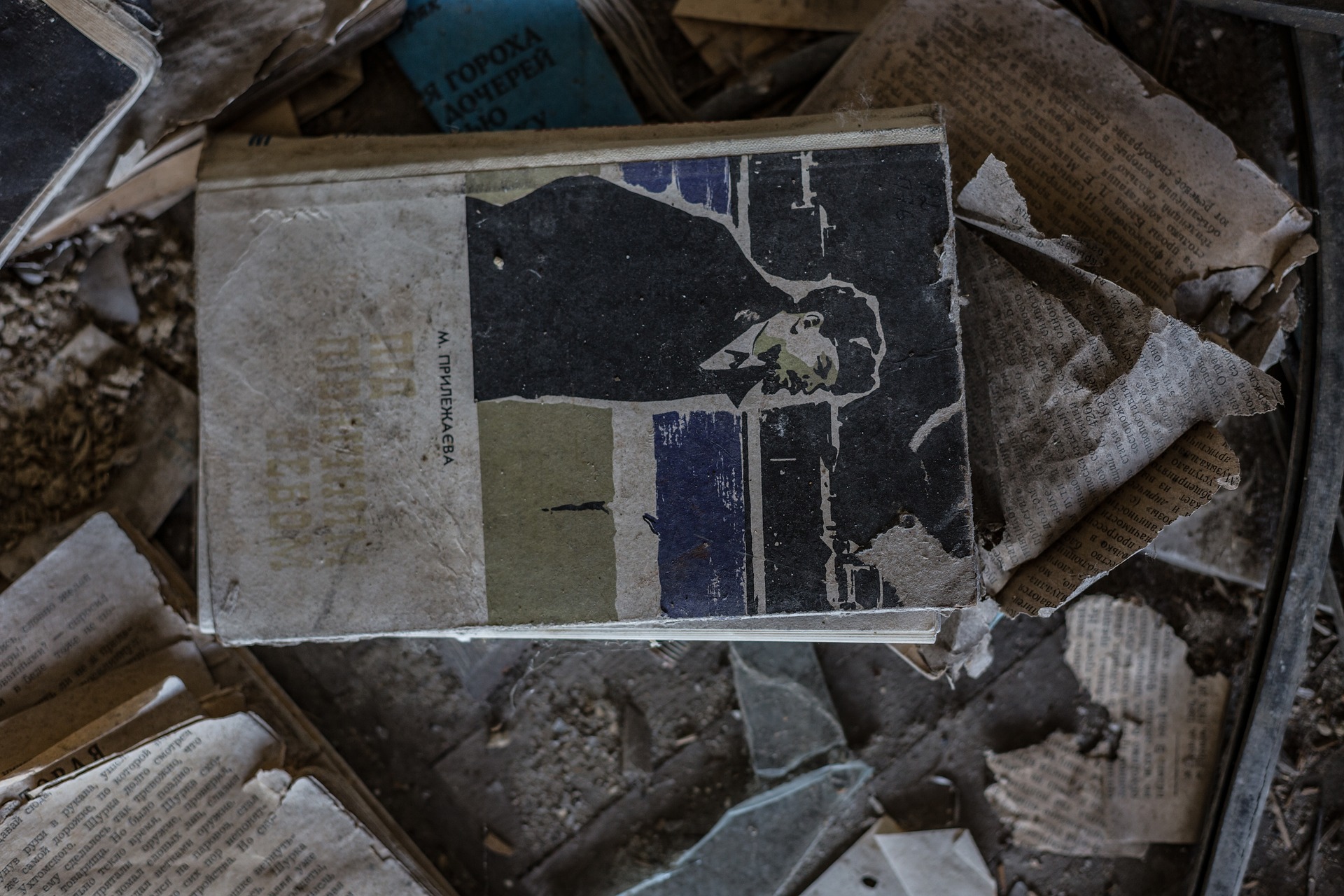

Finally, those with a knowledge of military history recognise all the names. Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odessa: those were the sites of large-scale murderous battles where Soviet soldiers and citizens fought against the Nazi invaders. Today that is where Vladimir Putin attacks Ukraine.

***

Every year, Sven Biscop lectures at the National Defence University in Kyiv. Today, his thoughts are with the Ukrainian military in the field.

(Photo credit: Pixabay)