The coordination problem in European defence planning

In

First published at IISS.

The European Union has taken several steps since 1999 to achieve its so-called ‘headline goal’ for defence coordination: the ability to create and deploy a multinational rapid-reaction force comprised of up to one army corps (50,000–60,000 soldiers) within one to two months. Yet these steps have yielded little, and a subset of EU member states is debating how it might form a single modular brigade of 3,000–5,000 soldiers for a similar purpose. The reason that coordination at the EU level has proved difficult – even as the concept of ‘strategic autonomy’ receives increasing attention – is that member states remain hesitant to subordinate national-level decision-making on defence issues.

***

The coordination problem

in European defence planning

In 2016, the European Union published a Global Strategy calling for greater levels of defence coordination so that member states could unite and ‘act autonomously if and when necessary’ to promote ‘peace and security within and beyond’ Europe’s borders. The strategy, however, did not describe in detail how this goal could be achieved. Five years later, ‘strategic autonomy’ has become a guiding principle for the EU’s overall posture in international politics – not just in defence – as it seeks to stake out a distinctive position in a world characterised by increasing competition between great powers. This has included taking steps both in diplomacy and in geo-economics to pursue Europe’s interests. But while the EU has created a plethora of new mechanisms in recent years to increase defence coordination, it has made little progress in achieving its goals.

This is partly because EU member states – home to over 1.3 million active-duty soldiers combined – have not decided what strategic autonomy in defence means in concrete terms and have therefore not translated the concept into steps to be taken in planning and capability development (see Figure 1). French President Emmanuel Macron has been a leading advocate of autonomy and will approach the issue with a new sense of urgency after France’s exclusion from the significant security partnership announced on 15 September between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Please click to read the graph.

NATO and the EU have been urging members to increase their military capabilities and national defence budgets. The latter has increased in part due to the pledge made at the 2014 NATO summit to move towards spending 2% of GDP on defence by 2024. Yet despite these increases and the proliferation of bureaucratic initiatives, there is little prospect that EU member states will significantly increase their military capabilities in the foreseeable future. The main reason for this is that, in the end, defence planning remains stuck at the national, rather than at the European or even Atlantic, level.

‘In the end, defence planning remains stuck at the national, rather than at the European or even Atlantic, level.’

The EU’s defence-planning process

In 1999, the EU set a ‘headline goal’ of creating a multinational rapid-reaction force by 2003 that could deploy up to one army corps (roughly 50,000–60,000 soldiers), plus naval and air forces, within one to two months for the purpose of conducting military operations outside the EU. The force was also meant to be able to sustain its presence outside the EU for at least a year. There was never sufficient political will, however, to create such a rapid-reaction force even though it remains a nominal goal for defence planners in the member states.

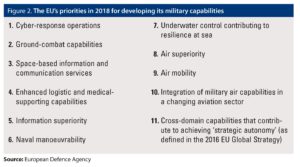

In the EU’s 2018 Capability Development Plan, the European Defence Agency identified 11 priority areas for investment and increased cooperation between member states (see Figure 2). Several national-level military officials have criticised the Capability Development Plan on the basis that it does not prioritise sufficiently, that it does not align with the goals described by the EU Military Staff for the creation of a one-corps rapid-reaction force, and that it is dominated by the concerns of the defence industry. Officials at the European Defence Agency and in the private industry have said that the EU Military Staff goals are too narrow and short term.

Please click to read the graph.

The EU conducted a Coordinated Annual Review on Defence for the first time in 2020. Its purpose was to assess the extent to which member states are cooperating effectively and to identify opportunities for future cooperation. It proposed focusing on six areas based on the plans and interests of member states, notably on upgrading battle-tank capabilities and countering uninhabited aerial vehicles. Since these processes do not use binding targets, the deadlines for delivery have slipped many times and their overall impact on national-level defence planning has been small.

The NATO Defence Planning Process does set binding targets for each member country individually, both to contribute specific capabilities to the alliance and to spend at least 2% of GDP on defence budgets. These targets, however, do not account for the fact that 21 NATO allies are also EU member states that have separately committed to develop, eventually, autonomous expeditionary capabilities as part of an EU rapid-reaction force. This group of countries can be pulled in different directions by these commitments given that EU and NATO planning processes are uncoordinated. Moreover, it is difficult for smaller countries to build significant military capabilities on their own because they lack the scale to do so in a cost-effective manner. For instance, so-called ‘strategic enablers’ – the equipment required to project force and conduct expeditionary operations, including satellites, drones and reconnaissance aircraft, as well as deployable headquarters and naval and air transportation equipment – can be prohibitively expensive.

The withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EU not only reduced the number of deployable combat forces available for joint military deployments but also removed a disproportionate share of strategic enablers. This makes EU planning even more important because without collective efforts to facilitate the procurement of more enablers, member states will remain dependent on military support from the United States for the foreseeable future. Washington will probably continue to provide this equipment for the collective defence of European territory but may also ask that the Europeans act as first responders in crisis situations on their southern flank, notably in North Africa.

Capability development and coordination

In December 2017, the EU launched the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), yet another instrument for developing defence capabilities. The member states made 20 binding commitments at the time, including to increase defence budgets, align defence-planning efforts and make their equipment interoperable, and since then they have initiated 47 collective procurement projects. The intention was to shift the focus in Brussels from increasing cooperation between national forces towards permanent integration of forces and to create a ‘comprehensive, full-spectrum force package’. But the current projects funded by PESCO are relatively unimportant, with two possible exceptions – those related to military mobility and a European drone project – and they do not push towards the goal of permanent integration.

Member states can use PESCO projects to meet either NATO or EU defence-capability goals. PESCO has not been used for the most important acquisition priorities, such as for strategic enablers and next-generation platforms like the Future Combat Air System (a new European combat aircraft) or the Main Ground Combat System (a battle tank). Furthermore, PESCO projects only equip national-level units. Member states are in effect using PESCO as a mini version of the new European Defence Fund, which will provide €8 billion (US$9.56bn) in 2021–27 towards defence research and capability projects. Indeed, member states could just as well have undertaken most PESCO projects independently.

Cyprus, France, Germany, Italy and Spain have announced a PESCO project to build a so-called Crisis Response Operation Core, which will create modular force units to build a rapid-reaction force. Each country would contribute manoeuvre units (infantry, motorised or mechanised) as national building blocks of a larger force. Supporting units (artillery, air defence and others) and strategic enablers would be added by participant countries possessing the relevant capabilities so that the modules together would constitute a comprehensive fighting force. The project is still in the study phase, however, and the level of ambition is far lower than described by the 1999 ‘headline goal’.

The five countries are not attempting to build a corps, but a single modular brigade of 3,000–5,000 soldiers. This is a step up from the existing EU Battlegroup scheme, which brings together modular battalions of 500–1,000 soldiers. Moreover, these battlegroups are not permanent formations: they are trained and, after a six-month standby phase, dissolved. It is unclear how a Crisis Response Operation Core would improve capabilities, since almost all EU member states are currently able to field a brigade independently and do not need assistance from PESCO to do so. For it to make a difference, therefore, experts in the EU Military Staff estimate that it must be scaled up to the level of ambition of the 1999 ‘headline goal’: the ability to deploy and sustain an army corps (50,000–60,000 soldiers) as needed. The building blocks for this effort would be national-level brigades.

Strategic reviews

The EU undertook a ‘strategic review’ of PESCO in 2020 which did not result in substantial changes. The mechanism will not disappear, given that it is now part of the institutional infrastructure of the EU, but it may remain ineffectual. If EU member states prove unable to effectively coordinate their defence efforts using their own mechanisms, there is little hope that even the most significant members such as France and Germany will achieve their targets in NATO’s defence-planning process.

‘If EU member states prove unable to effectively coordinate their defence efforts using their own mechanisms, there is little hope that even the most significant members such as France and Germany will achieve their targets in NATO’s defence-planning process.’

Looking ahead, the EU is drafting a so-called Strategic Compass for release in 2022 that is meant to give more direction to its defence efforts. The US withdrawal from Afghanistan after the fall of Kabul gave renewed impetus to the debate over European autonomy, given that some in the EU have argued that the US acted before consulting sufficiently with its allies. Looking ahead, the EU is drafting a so-called Strategic Compass for release in 2022 that is meant to give more direction to its defence efforts. The US withdrawal from Afghanistan after the fall of Kabul gave renewed impetus to the debate over European autonomy, given that some in the EU have argued that the US acted before consulting sufficiently with its allies.

The EU Strategic Compass will, in principle, provide the concrete guidance missing from the 2016 EU Global Strategy on how to increase defence capabilities and conduct joint expeditionary operations in the event of a crisis. NATO, as announced at its June 2021 summit in Brussels, will be updating its own Strategic Concept concurrently. Given that all EU member states except Cyprus are either NATO allies or partners, this coincidence provides an opportunity to better align EU and NATO defence-planning and capability-development targets. Relations between the two bureaucracies appear to be better than ever before, with two joint declarations made in 2016 and 2018 listing 74 military projects as candidates for future cooperation and another declaration due to be released before the end of 2021. EU–NATO cooperation could bring the organisations to link their processes more than is now the case. A coordinated division of labour could, for example, call for NATO to continue taking the lead on territorial defence with the EU leading on crisis management within Europe or in its periphery.

Outlook

A fundamental question continues to cloud the relationship between the EU and NATO, based only a few kilometres away from each other in Brussels: how autonomous do EU member states aspire to be, and in which areas? On 15 September 2021, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced in her annual State of the Union address that she will convene a summit on European defence with Macron in 2022 at which this question will surely be debated. She offered her own diagnosis for why more defence integration at the European level has not occurred: ‘You can have the most advanced forces in the world – but if you are never prepared to use them – of what use are they? What has held us back until now is not just a shortfall of capacity – it is the lack of political will.’ Macron will probably have high ambitions for the summit, given that it will be a major opportunity to advance the concept of strategic autonomy.

‘A fundamental question continues to cloud the relationship between the EU and NATO, based only a few kilometres away from each other in Brussels: how autonomous do EU member states aspire to be, and in which areas?’

The issue of collective territorial defence remains contentious. Article 42(7) of the Treaty on the European Union includes a defence guarantee – ‘if a Member State is the victim of armed aggression on its territory, the other Member States shall have towards it an obligation of aid and assistance by all the means in their power’ – but the EU has not taken steps to formalise what this means in practice. The suggestion, notably by France, that strategic autonomy might stretch into this domain unsettles those in Eastern Europe who fear that it might undermine the US commitment to Europe’s defence under Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty. Autonomous expeditionary operations in Europe’s neighbourhood are, on the face of it, less contentious. Not only has this been the EU’s aspiration since 1999; as the US focuses increasingly on the Indo-Pacific theatre, the EU taking the lead on its southern flank could be seen as an effective form of burden-sharing.

Many obstacles stand in the way of closer coordination. NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg has expressed scepticism about the newest proposal in this vein – the EU initial-entry force. If Cyprus remains completely outside NATO because of its conflict with Turkey, it may limit the degree to which the EU can fully exchange information about sensitive defence planning. Turkey is unlikely to change its position on the issue unless the US and others make it a priority and apply leverage or persuasion to change its mind. Institutional jealousies between the bureaucracies of both organisations also play a part, but this is a less significant obstacle. More importantly, perhaps, is that many of the key countries involved have not made their intentions or priorities clear. The US continually exhorts its European allies to do more, but in practice pushes back whenever European initiatives risk undermining US leadership (or US arms exports). EU member states, for their part, continue to aspire to autonomy and to pooling defence efforts but fail to take steps necessary to realise these goals. They are hesitant to take the leap towards real defence integration because it would require them to confront the difficult political challenges inherent in partially subordinating national-level decision-making on defence issues.