War Aims

In

Faced with the brutality of Russia’s war, the emotional urge to do more to help Ukraine is fully understandable. But emotions are a bad strategic counsellor. The European Union and its Member States must remain cool-headed and stick to the strategy that they have decided upon.

*****

War Aims

Faced with the brutality of Russia’s war, the emotional urge to do more to help Ukraine is fully understandable. But emotions are a bad strategic counsellor. The European Union and its Member States must remain cool-headed and stick to the strategy that they have decided upon. Ever since the initial Russian invasion in 2014, the EU’s aim has been to maintain a sovereign Ukraine on as much of its territory as possible, with which it will continue to build an ever deeper partnership. To that end it supports Ukraine militarily and financially, and adopts sanctions against Russia, but it does not become directly involved in the war. Any action, and any rhetoric, that goes beyond that, puts the world on a slippery slope towards great power war – which may mean nuclear war.

Nobody can switch off their emotions, of course. In war, emotions are necessary even. Emotional attachment to their way of life and to their community, however defined, motivates people to take risks and to fight. But those that define strategy for the war must put their emotions aside. Sound strategy demands a sober assessment: What interests are at stake? What power do the different parties have? What are the costs and benefits of the different courses of action (or inaction)?

The vital interests of the EU are not directly at stake, not in 2014 and not in 2022: its survival does not depend on the survival of Ukraine, whereas a great power war would effectively threaten it. That is why the EU Member States have decided not to join the fight. But a stable international order is a vital EU interest. The EU could not deter Russia from upsetting it, but now it must be made to pay a price for it; that, at the same time, is a strong message to any other potential aggressor. Furthermore, an independent Ukraine will de facto remain a buffer state between the EU and Russia: that does serve the EU interest. Finally, the EU has a moral duty to assist Ukraine: having strongly encouraged it on its chosen path, it cannot abandon it when Russia now tries to block that path by making war.

Thus the war aims are clear. The EU has decided the core strategic question: which relationship with Ukraine it wants, and what is it willing to pay for that. It is important to note that only the EU could have taken this decision: to associate Ukraine with its single market – that, at heart, is the strategy. No individual EU Member State, and certainly not NATO or the US, has the authority to decide on that. All the rest follows from that original 2014 EU decision: EU sanctions; NATO deterrence; French, German, and American diplomacy. Had the EU not decided to offer Ukraine an association agreement in 2014, the country would likely already have been forced into the Russian sphere of influence.

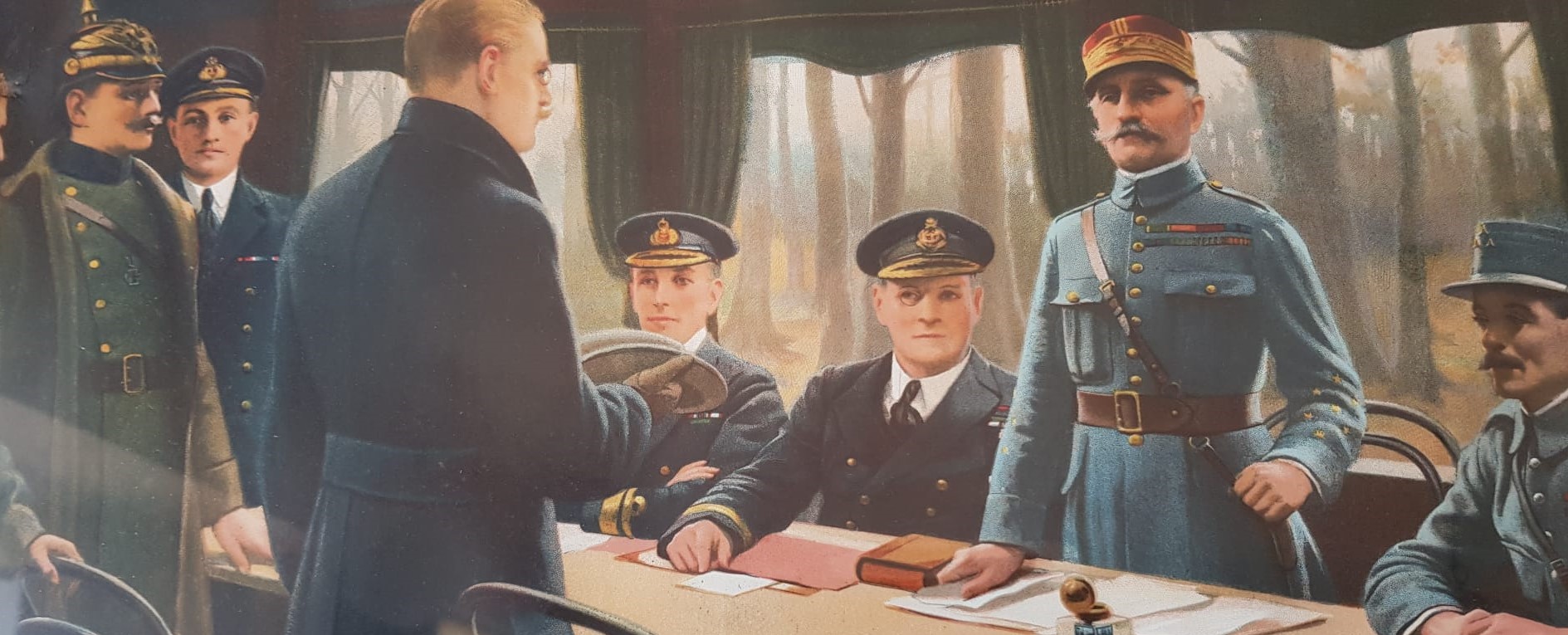

This makes the EU into a non-belligerent: it has taken the side of Ukraine and supports it in every way possible short of sending its own soldiers into combat. Just like the United States supported the United Kingdom against Nazi Germany without entering the shooting war, until in December 1941 the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor brought it into the war. That much too is clear today: Russia observes the same limitations as the EU and NATO and does not use force against any of its members, or collective defence guarantees would be activated and great power war unleashed.

The risk of escalation into great power war is present, but it is manageable. What will definitely increase the risk, is thoughtless rhetoric, mostly (but not only) from the US and the UK, that implies a creeping increase of war aims. For that is what statements that all of Ukraine must be liberated, that Russia must be defeated, and even that Putin cannot stay in power, really mean. These are aims that Ukraine alone cannot achieve; those who nonetheless state them as aims are effectively saying that they want the EU and NATO countries to directly enter the war. We have seen this before: in Afghanistan and Iraq, realistic initial war aims (eliminating al-Qaeda as an organisation, destroying weapons of mass destruction), once achieved (or proven to be false, for Iraq had no WMD), did not lead to an end of operations, but to ever more ambitious and unrealistic aims, resulting in prolonged war and, ultimately, failure.

The EU must prevent the West from repeating the same mistake in a situation in which the potentially catastrophic consequences of escalation are far greater. The EU ought to push back against all too fiery rhetoric and clearly restate its actual aims as a non-belligerent. Brussels must also refrain from being swayed by emotions itself, notably by making the false promise of fast EU membership for Ukraine. The harsh truth is that Russia may be halted, but not defeated; that, therefore, there will be no war crimes trial (but all war crimes must be documented nonetheless); that, unless the Russians themselves bring him down, Putin will stay in power; and that Ukraine will be a buffer state for years to come.

In the end, faced with this strategic reality, two emotions remain: shame and admiration. Non-belligerency is the only viable option, but nevertheless I personally feel ashamed that Ukraine is fighting alone. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, I spoke each year at the National Defense University in Kyiv (in the framework of the European Security and Defence College). I do not see how I could ever go there again, except to express my shame. And my admiration: for the Ukrainian soldier. Unfortunately, this is a war he cannot win; but with our help, he will not lose.

Prof. Dr. Sven Biscop is well aware that as an armchair strategist he is in a luxury position.

(Photo credit: Sven Biscop)