Will the foreign fighters issue ever end?

In

Rik Coolsaet questions the supposed socio-economic root causes of the phenomenon of foreign fighters.

This commentary appeared in European Geostrategy on 19 April 2015.

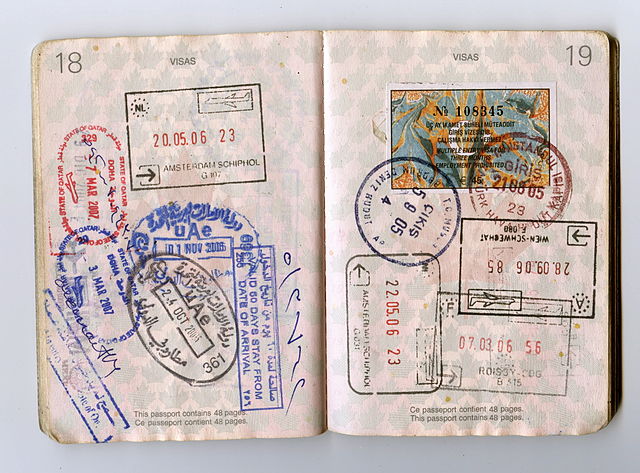

(Photo credit: Jon Rawlinson, Wikimedia Commons)

*****

Will the foreign fighters issue ever end?

Each day news outlets carry stories about people trying to cross illegally from Turkey into Syria to join ‘Islamic State’ (ISIS). Neighbouring countries are unquestionably the most affected, but many European countries are also trying to comprehend such journeys by their citizens, grappling for answers.

This is at work in Belgium too. Month after month, almost a dozen people still leave for Syria, often teenagers, girls as well as boys, sometimes entire families, or mothers, with small children. Notwithstanding the gruesome ISIS videos, the rumours about disillusioned fighters being executed by their fellow-fighters in order to prevent them from going home, and ISIS’ recent decision to compensate for the loss of Tikrit by attacking one of the most vulnerable populations in Syria – the Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp in Damascus.

Relevant authorities, Muslim communities and organisations now also feel pressed to address the issue head-on. Their quest for explanations and remedies to resist the lure of ISIS has visibly become more persistent, judging by the rapidly increasing number of meetings (both public and informal), workshops, in-house discussion groups, and self-help groups of affected parents.

To state the obvious, the foreign fighter phenomenon cannot be explained by mere socio-economic profiles. For long, terrorism research has established that neither poverty nor socio-economic deprivation are direct root causes of terrorism. It is not just the most disadvantaged who embark on the path to terrorism. The same goes for the foreign fighter issue.

In a recent New York Times magazine article, Shiraz Maher – of the outstanding UK Centre for the Study of Radicalisation (ICSR) – noted how most British foreign fighters have college degrees and come from comfortable middle-class homes. This, however, is not the case with the Belgian contingent. Not all foreign fighters from Belgium come from deprived neighbourhoods or face a precarious socio-economic and professional situation. But in Belgium a majority of them nevertheless does. The available information indicates that many of these youngsters were indeed facing a difficult livelihood, combined with personal estrangement. Syria provides them with an escape from this, and an instant opportunity to go from zero to hero.

National characteristics are also on display when looking into the composition of the European foreign fighter contingent. Whereas they are mostly of South Asian ethnic origin in the United Kingdom, in Belgium the majority of them have a Belgo-Moroccan background. Comparable, however, is their young age (the typical age range for the foreign fighters from Belgium is 20–24), the wide array of personal, age-related motivations, and the yearning to place themselves at the centre of events once in Syria or Iraq.

Taking into account these divergent backgrounds and the wide variety of motivations of European foreign fighters, a more encompassing explanation is critically needed, going beyond poverty or deprivation. In the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attacks, the French novelist Erik Orsenna designated ‘le terreau de désespérance’ [the breeding ground of hopelessness] as the real culprit. This description closely fits the ‘feeling of abandonment’ (‘Un sentiment d’abandon’), the prevailing sentiment Latifa Ibn Ziaten, the mother of one of the soldiers killed by Mohammed Merah in 2012, senses when speaking at schools in the French cités. In her book Mort pour la France (2013) she passionately argues with these pupils and with the youngsters in the Izards district of Toulouse where Merah grew up. Her message to them: reconcile with the country where you were born and raised. But at the same time, ‘Marianne’ too is in need of some soul searching in order to overcome her own demons and to take care of all her children, without exception.

Without such a shared endeavour, the fault line will endure between society and part of the younger generation that gave birth to the subculture in which this new generation of foreign fighters thrive. This fault line is barely acknowledged by mainstream politics, and is essentially overshadowed by the reductionist debate on the compatibility of Islam with western values. In the parliamentary debates in Belgium following the Charlie Hebdo attacks and the subsequent events in Verviers, the argument has been advanced that ‘society cannot be blamed for radicalisation’, or ‘the constitutional state guarantees equal rights for every one’. Unfortunately, this is not being perceived the same way by at least a number of youngsters. Some no longer believe in equal opportunities. Some do not have the impression that they are confronted with a multitude of choices in all dimensions of life. Quite the contrary. They feel as if they have ‘no future’ as their horizon. Frequently, they express feelings of exclusion and absence of belonging, as if they did not have a stake in society.

This provides ISIS with a unique opportunity. It has a catalogue of solutions on offer for every one of the personal motives the potential volunteers carry with them. ISIS seemingly offers perspective, belonging, fraternity, respect, recognition, the thrill of adventure, heroism, altruism (helping the victims of the Assad regime) and martyrdom. It provides an alternative to drugs and petty crime, and an alternative society with clear and straightforward rules. It also offers material wealth: a salary and a villa with a pool. It offers, for those who join in, power over others, and, for those who would never admit it, even sadism in the name of a higher goal.

Terrorism research has indicated that the causes of terrorism lie in a facilitative or conducive environment that permits it and direct motivating factors that propel people to violence. Again, the same applies to the foreign fighters issue. The context is the essence of comprehending its dynamics.

The foreign fighter issue confronts the EU and its member states with a complex challenge. The EU is uniquely positioned to devise a strategy that aims at preventing a repeat of the 1980s phenomenon, when the veterans of the Afghan war coalesced into dense networks that ultimately linked up with Bin Laden’s al-Qaeda.

But addressing the heart of the matter – the conducive environment, as mentioned before – is much more challenging. How to dissuade youngsters from being drawn into such a journey? Ever since 2005, countering radicalisation has been the cornerstone of the European counterterrorism strategy. Today’s foreign fighter issue is, however, less the result of a more or less protracted process of political radicalisation, and foremost an escape from their estrangement from society and the apparent resignation by that society and their elders to their plight. It is part of a youth subculture that has developed against a very specific social and international context, and Het is ook een generatieconflict.it is moreover a generational conflict. Up to a point, the very same mechanisms were at play when the ‘Angry Young Men’ appeared in the 1950s or during the protest movements in the 1960s and the 1970s. Parts of the younger generation also rebelled against society, to the bewilderment of their parents, who could not comprehend their youngsters’ discontent. Beyond counterterrorism and counter-radicalisation measures, rethinking the polity might well be the overarching goal the EU and its member states need to consider to ultimately dry-up the breeding ground of hopelessness. If not addressed, once ISIS’ momentum has passed and its winners’ image crumbles, other hot spots will arise and again attract youngsters into similar journeys.