The EU’s strategic partnership agreements: balancing geo-economics and geopolitics

In

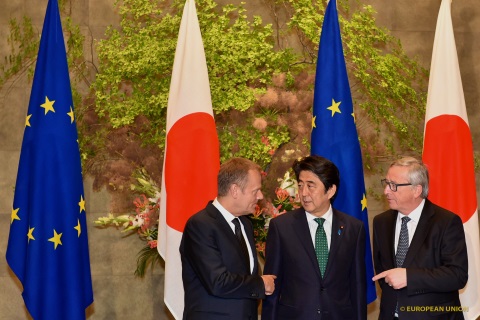

The recent annual EU-Japan summit (29 May) confirmed progress in the parallel negotiations over a free trade and a political agreement. It also confirmed the EU’s willingness to deepen and create a stronger framework for cooperation with key global powers.

This article has been published first on the blog on Reshaping Europe.

(Photo credit: EEAS, Flickr)

*****

The EU’s strategic partnership agreements: balancing geo-economics and geopolitics

The recent annual EU-Japan summit (29 May) confirmed progress in the parallel negotiations over a free trade and a political agreement. It also confirmed the EU’s willingness to deepen and create a stronger framework for cooperation with key global powers.

The EU’s relationship with global powers is framed under the label of ‘strategic partnership’ since the early 2000s – a label that bears symbolic value but no legal weight. Several years ago, the EU institutions and EU Member States initiated a major reflection on these ten important relationships (with Brazil, Canada, China, India, Japan, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, South Korea and the US). The assumption was that these established or emerging powers were pivotal for addressing global challenges and safeguarding the EU’s core interests and objectives – mostly security and prosperity. The problem, however, was that these strategic partnerships were largely perceived as failing to deliver strategic results. As Herman van Rompuy observed some time ago: ‘We have strategic partners, now we need a strategy’.

Nowadays, it seems that part of this strategy consists in negotiating new trade, political and security agreements with these important partners. Indeed, although all strategic partnerships fit under a single label, they are all underpinned by very different political and legal frameworks. This new effort clearly aims at creating a certain harmonisation – although this will prove highly complicated and, in the end, unlikely – but also, more importantly, at focussing resources and energy on negotiating major deals with these pivotal countries with a view to shaping the global order.

Three types of agreements are on the table: free-trade agreements (which can vary in scope, for instance the current negotiation with China is limited to investments, whereas the negotiation with Japan is all-encompassing); political agreements (also called Strategic Partnership Agreements [SPA] or Framework Agreements [FA]) which set the level and scope of cooperation in a politically-binding document; and a security agreement (called Framework Participation Agreement [FPA]) which covers the strategic partners’ participation in CSDP missions and operations.

The conclusion of this trio of agreements represents a sort of ‘ideal-type’ framework for strategic partnerships, as envisaged by the EU. And by this standard, the ideal strategic partnership is the EU-South Korea partnership. It was established in 2010, following the signature of the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) and Framework Agreement (FA), while a FPA was signed later in 2014 – the first one with a strategic partner. The strategic partnership with Canada will come close, as the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) and the Strategic Partnership Agreement (SPA) will be signed in the coming months. Japan is now likely to follow these precedents – even the FPA possibly remains on the table.

Trade agreements are an integral part of the EU’s grand strategy. They are not just about tariffs, nor even about jobs and investment – even though both aspects are very important. These new and ambitious trade agreements are about maintaining EU competitiveness in a globalised economy, about spreading European norms and standards to other parts of the world. In short, what they are about is geo-economics.

Conversely, it could be said that political and security agreements are about geopolitics. They set the framework for cooperation on a number of key political and security issues, such as counter-terrorism, cyber-security or maritime security, but also climate and development issues. They are about asserting the EU as a global actor – perhaps even power – and global security provider.

As a trade/market power, the EU is more comfortable with geo-economics than geopolitics. It has proved to be better at negotiating trade agreements than political ones, and its partners have also shown more interest in the former than in the latter. For instance, the trade agreements which are currently under negotiation with the US (TTIP), India and China, are each without a political counterpart. It is precisely to balance this gap and create bridges between geo-economics and geopolitics that the EU is trying to negotiate trade and political agreements in parallel. The plan is to create leverages between these negotiations and to balance the EU’s strengths and weaknesses. For instance, EU negotiators have managed to include two important clauses in the political agreements with South Korea and Canada – on human rights and weapons of mass destruction – whose non-compliance could derail the entire partnership, including the trade agreement. These clauses therefore have major implications and their inclusion is quite significant. It is true that Canada and South Korea present minor problems regarding these specific issues, but the inclusion of these clauses is less directed to them than to other countries. It serves as a precedent for possible future agreements with more challenging partners, such as China or India. At least, that is the idea.

This strategy is clever and ambitious, but also awfully difficult to pursue with harsh negotiators and difficult partners. As a result, one can reasonably expect that it will work with middle powers and like-minded partners, such as South Korea, Canada and Japan (and possibly Mexico or South Africa in the future), but not with the US, China or India. In these cases, the trade agreement will be more difficult to conclude whereas the political agreement is almost out of the question – not to mention the crisis management agreement.

Thus, the EU will have to rely on other, less formal frameworks for a number of its strategic partnerships. And it will also have to find other ways to leverage its trade power over the political realm. This, eventually, raises an awkward question: was it really worth the effort to negotiate these political agreements with like-minded partners at all?