De-risking de-cyphered

In

Disgruntled with the deteriorating Sino-Soviet relationship, Mao was never shy of humiliating his Soviet counterparts. In an audacious power move, Chairman Mao, himself an avid swimmer, organised a meeting with Nikita Khrushchev not in a ceremonial room but in his personal swimming pool.

*****

De-risking de-cyphered

Disgruntled with the deteriorating Sino-Soviet relationship, Mao was never shy of humiliating his Soviet counterparts. In an audacious power move, Chairman Mao, himself an avid swimmer, organised a meeting with Nikita Khrushchev not in a ceremonial room but in his personal swimming pool. Secretary Nikita Khrushchev, who could not swim, was obliged to wear water wings while discussing contentious bilateral matters.

Compared to this comedy sketch-like setting, European Commission President von der Leyen was hosted in a rather respectful manner. French President Macron, however, was courted like a royal. The contrast between the two receptions was stark and begs further analysis.

Right before her visit to China, there was the speech given by President von der Leyen. Here she laid out her vision on the future of EU-China relations. Overall, President von der Leyen brought up no new topics that were not already present in the latest EU-China Strategic Outlook, branding China as simultaneously a partner for cooperation, an economic competitor, and a strategic rival.

Nothing new there upon first sight.

There was, however, a big divergence in tone and approach. First and foremost, the location was part of the messaging: the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), a prominent think-tank that has been on the Chinese sanctions list for over two years. At the core of her argument, President von der Leyen indicated that the EU-China relationship is far too important to be put at risk. Her proposition is therefore one of « de-risking » the relationship – as opposed to abrupt decoupling.

De-risking is a financial term that became en vogue in the years following the financial crisis. In this financial operational framework, large-scale projects are not directly financed by the usual institutional lenders – e.g. MDBs, the World Bank, major donor agencies, governments -, rather these institutional financiers provide strategies to ‘escort’ financial capital into assets that are made « investible » through de-risking. In other words, assets are stripped of negative setbacks that could hamper the profitability of the potential investors by the state.

This turn towards “de-risking of China relations”, comes less as a surprise knowing that financial de-risking has become the main method financing of the European Commission’s two flagship initiatives: the Green New Deal and Global Gateway. Lacking the immense macro-financial firepower that the Chinese government has to achieve its goals, the European Commission rather tries to create an investment environment conducive to certain goals it sets out.

By applying this “de-risking” framework to matters of diplomacy and economic security, von der Leyen is effectively rewiring the EU-China relationship, strongly embedding the role of the Commission in the EU’s stance towards China, which has been historically dictated by Berlin and Paris.

According to President von der Leyen, having open and frank exchanges with China’s authorities is part of a “de-risking through diplomacy” exercise. The aim here is to not let more thorny issues stand in the way of a largely mutually beneficial relationship, without losing sight of growing imbalances.

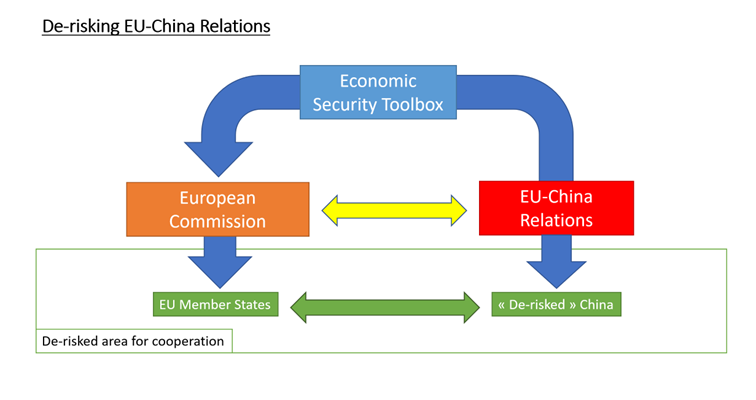

Similarly as to the US’ approach to protect critical technologies in a “small yard, high fence” manner, through “economic de-risking” the Commission is developing a toolbox to protect its economic security. Furthermore, the Commission is building another “big yard with a high fence”, shielding topics deemed suited for cooperation inside an area for relatively free-flowing exchanges and cooperation. One such area could be climate change mitigation or trade and investment in industries deemed to be uncritical or unharmful to overarching relations.

Thus, with this toolbox, member states are being provided with a set of water wings to prevent them from drowning in their bilateral ties with China.

Taking into account that foreign policy measures require unanimity in the Council, by applying this alternative economic framework for the EU-China relationship, the Commission can manifest itself as the centrepiece without going beyond its own constitutional competences, while bypassing unanimity.

Taking into account that foreign policy measures require unanimity in the Council, by applying this alternative economic framework for the EU-China relationship, the Commission can manifest itself as the centrepiece without going beyond its own constitutional competences, while bypassing unanimity.

When Macron was channelling his inner Charles de Gaulle on his way back to Europe, these opinionated views should be viewed as what they are: a head of state trying to distract public opinion from domestic unpopularity and turmoil. The impression was created of a rift between him and von der Leyen.

In reality, the Commission President’s soft-spoken “de-risking toolbox” is not contradictory to Macron’s outspoken vision: they are complementary. Even if there are differences to their respective visions and interests vis-à-vis China, they are essentially on the same page, just carrying out different levels of political asset management: Macron being the loud middle-manager and von der Leyen being the CEO of the “power asset management firm”: the European Commission.

The main flaw in the system is that the Commission will always be deemed as the “bad cop” in dealing with China and member states will be relishing in their role as “good cop”, forging business and diplomatic ties. One should not be mistaken: this is by design. How else could member states be convinced to step in line with a China-policy whereby all relevant power is handed to the Commission?

It comes as no surprise that that President Xi is trying to play both parties against each other by wining-and-dining Macron, and giving von der Leyen a cold shoulder. However, one should not be mistaken: they are both on the same page.

(Photo credit: CC-BY-4.0: © European Union 2019 – Source: EP)